December 23, 2019

This is the fourth in a series of guest blogs by the 2019-20 Michigan Regional Teachers of the Year. Jeremy Winsor, an earth science, biology and environmental science teacher at Fulton Middle School-High School in Fulton Schools, is the Region 4 winner.

This is the fourth in a series of guest blogs by the 2019-20 Michigan Regional Teachers of the Year. Jeremy Winsor, an earth science, biology and environmental science teacher at Fulton Middle School-High School in Fulton Schools, is the Region 4 winner.

I have always enjoyed the outdoors. This enjoyment has led to my interest in teaching the content that I currently do. I have a love for the biological and earth sciences. It is refreshing being in nature, but nothing gets me more excited about being outside than standing waist deep in one of Michigan's cold water trout tributaries.

There is something rejuvenating about sneaking through a babbling brook with the intention of feeling the pull of the elusive trout on the other end of my line. The echo of a pileated woodpecker drilling into a deteriorating conifer to find its next lunch or the far off bleat of the newly minted whitetail deer fawn are always welcome interruptions.

Being in the wilderness and bearing witness to the order of the natural world always gives me pause. The pause leads to deep reflection. Reflection on life can be observed everywhere in its various forms, but there is also reflection in teaching and learning. I love that the natural order of things can teach without saying a word, and so, I reflect on how I, too, can do the same.

Building Inquiry Builds Excitement and Gives Ownership

As an undergraduate, I had a professor who would often make the statement, “Be a guide on the side, not a sage on the stage.” For much of my professional career, I struggled with what that looked like in practice. Maybe it was my inability to relinquish control or a fear of what I envisioned as the chaos that could occur if I chose to relinquish that control. Either way, I spent years dabbling in it without truly handing over the ownership of learning to my students.

It wasn’t until I first became a learner in a true inquiry classroom that I was able to give my students that power. As educators, we can start this process by simply allowing our kids to explore. Give them the opportunity to make sense out of the next science lab, social interaction or math equation with minimal guidance.

My entire class is set up on that premise that students will observe a phenomena before delving into the content and only assign vocabulary after they have a working understanding of what they have observed. One of my favorite activities for my biology students is the “Lazy Lizard Lab.” I was introduced to this lab through a three-week workshop that was facilitated by the American Modeling Teachers Association (AMTA). Students have various lab stations where they compete for resources. Each lab station has a different type of environment holding water. Students use straws and their hands to draw out water from the environment.

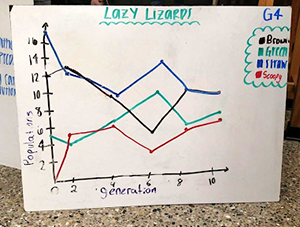

Ultimately the lab is a game that has a substantial amount of competition as students are trying to get a greater amount of water than their peers. After each round of feeding, students measure the amount of water that they collected and determine the highest feeder. The game continues where students exchange cards associated with their lizard skin color or other characteristics to represent reproduction. Ultimately this lab allows students to experience a simulated natural environment with competition, variation in environments, adaptation, microevolution, allele frequency changes over time and a whole host of other tie-ins.

After each day of the lab, I allow my students to “think pair share” and discuss their “noticings and wonderings.” In slightly larger groups, I have students use whiteboards and create a visual representation of their understandings. I tell my students that they should use charts and graphs, three-box storyboards, mathematical equations or any other visual to help explain their thinking. Finally, we display our boards for the group as a whole.

We call our class a “scientific community.” Students tend to take ownership of that description. I guide them as they question each other or the phenomena they are observing and use “sentence stems” to help students in their questioning. Like everything, practice is key and failure is inevitable, but “through failure we learn.”

As a teacher, I recognize that my students will be leaving my classroom. With that in mind, I feel it is my duty to help develop an inquisitive mind. Students should be asking questions based on observations every day. We live in a “Google era” of education where any question I can ask has the potential of being answered within a few seconds. This is a positive thing, however, what if my question can’t be quickly answered? What if I have to apply my previous knowledge to a novel idea?

This will be the future. Our students will need to use their understanding and apply it to new complex situations. They will need to solve some of the greatest problems mankind has ever faced. If I am not fostering a curious mind, building excitement in the unknown and helping my students to take ownership of their own learning, then I’m not sure I’m doing an effective job. Much like in our “Lazy Lizard Lab,” students should be given an opportunity to explore, adapt, modify and confirm their understandings. By guiding this process, I can confirm that my students are better prepared for a lifetime of learning.

As I slosh through a river or stream, I often reflect on how the natural world is related to my classroom. I process how the spinner or fly that I’m using is similar to the lesson that I have developed, with the intention to entice. There are times that the lure is effective, but there are also times that it is not. Some lures work on specific days but don’t on others. At times they are effective on specific fish but not others. Ultimately, I have concluded that like fishing, lesson development can take a massive amount of care and effort but may not entice all. It is the artistry in the presenter that “inserts the hook.”

As teachers, we all have times where we feel that a lesson should “insert the hook,” but it doesn’t occur. The natural world reminds us that we aren’t going to catch every fish every day. It’s the willingness to get up in the morning, grab our vest of hooks, squeeze into our waders and cast a lot of lures that ultimately lead to a successful experience. That successful experience might be on day 1, or it might be on day 180. We have to be willing to persevere.

There Is Value in the ‘Pause’

We are a hurry up society. We value speed and efficiency. “Time is money!” We scramble to finish the next task for the purpose of fulfilling a quota, gaining advancement or receiving the next bonus.

As teachers, we are guilty of this, as well. Often times we are expected to mimic a business model of production. We have to get to the next lesson, lab or activity, complete the next assessment, analyze the next piece of data, write the next grant, document the next behavior. The list goes on, rarely leaving time for pause. While there should be value in each of these things, I am concerned that without a “pause” we never truly appreciate where we are and where we are going.

If I don’t pause, I miss the sound of the fawn bleating in the distance, the pileated woodpecker carrying out its task, the undercut bank in the creek that I have so carelessly overlooked every other time I have traversed the same path. That structure might just produce the greatest amount of success or the largest trout I have ever bared witness to. Without pause, I am more likely to dredge though the water unaware of my surroundings, missing opportunities and potentially scaring everything along the way. As educators, we must take time to pause.

Reflection Requires Questions That Bring About Answers

“What am I doing and why am I doing it?” is a question that echoes through my head often. Without an ability to ask the right questions, I am unable to effectively reflect on my understanding and correct misconceptions. It goes deeper than that, though. As we reflect and question we ultimately are guided to answers, answers that in themselves construct new reflections and new questions. I find that I gain a deeper appreciation for the content that I don’t teach, and potentially didn’t enjoy as much in the past as I reflect and question. We can find value in the work of others as we discover that our frame of reference is small and collaboration is essential.

In fishing, my aim has always been to catch fish, but as I get older, I find that is only a minute portion of the experience. The time that I have to observe, reflect, and question while fishing have become the mainstage as I age. This in turn has led to an understanding. I understand that meaning comes from these experiences and application can as well.